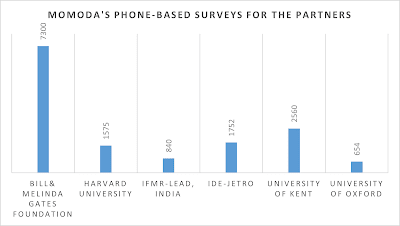

In this ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, MOMODa Foundation has

conducted telephonic interviews for 7 projects and reached nearly 15,000 respondents,

half of them are women. For collecting data from women, MOMODa Foundation has

also employed local women as surveyors/enumerators which constitutes more than

half of the total enumerators employed by the Foundation. Table-1

highlights MOMODa’s recent experience in telephonic surveys.

Table

1:

Telephonic

Survey Experience of MOMODa FOUNDATION

|

SN |

Project Name |

Sample Size |

Survey Area |

Affiliated Partner |

Project Period |

|

1 |

G2P COVID-19 Rapid Phone Survey |

7300 |

All over Bangladesh |

Bill& Melinda Gates Foundation |

May-Jul 2020 |

|

2 |

Telephonic survey on Spillover Effects of Hand Washing

Behaviors in Children - Phase 1 & 2 |

1575 |

Gaibandha |

Harvard University |

Jul- Aug. 2020 & Mar-Apr 2021 |

|

3 |

Micro-Entrepreneurs Survey in Bangladesh |

840 |

Dhaka, Khulna, Rajshahi, Mymensing |

IFMR-LEAD, India |

Aug-Sept 2020 |

|

4 |

Phone-based Household Survey on the Impact of

COVID-19 and Lockdown in Gaibandha

District in Bangladesh |

1752 |

Gaibandha |

IDE-JETRO |

Sept- Oct 2020 |

|

5 |

Collaborative Research Activities on the Effects of the

COVID-19 Pandemic in Bangladesh |

2560 |

Gaibandha |

University of Kent |

Sept- Oct 2020 |

|

6 |

Micro-equity and Mentorship for Online Freelancing Based

Micro-entrepreneurs in Bangladesh- COVID-19 Follow-up |

654 |

Gaibandha |

University of Oxford |

Oct-Nov 2020 |

|

|

Total |

14681 |

|

|

|

Table-1

shows that the MOMODa Foundation has carried out high-frequency phone surveys

on a range of areas including Hand Washing Behaviors, Micro-Entrepreneurs, Skill

training, and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. For these surveys, MOMODa made

phone calls all over the country especially for ‘G2P COVID-19 Rapid Phone

Survey’ and in terms of coverage, this project alone constitutes half of the

participants who have been interviewed by the MOMODa. However, in terms of

projects, the majority of them have been conducted in the Gaibandha district in the Northern part of Bangladesh to

understand the socio-economic impacts of COVID-19 on different groups.

During

the coronavirus pandemic, MOMODa research team has played an important role in

shaping the response to the crisis by collecting high-quality data through

phone surveys instead of relying on enumerators traveling to hear first-hand

accounts from communities. This note provides some insights from the MOMODa’s

experience with phone surveys in Bangladesh that research organizations may consider

when deciding whether to adopt such an approach:

1. The MOMODa research team found that phone surveys are

extremely effective because they do not require traveling, the method is quick

to administer, and they are well-suited for high-frequency data collection

campaigns designed to monitor variables in a population over a given time

period.

2. Phone surveys can reach a much larger sample than can be

achieved by sending enumerators to respondents’ houses, and at a much lower

cost. Additionally, the total number of mobile phone subscribers in Bangladesh has

reached 170.1 million at the end of December 2020. We found that despite

Gaibandha being a remote and rural area, almost every household has a phone set

which is a remarkable achievement in the way of digitalization of Bangladesh.

This has been advantageous for us to collect high-quality data through phone

surveys.

3. We also found that there is a lack of access to a phone

in rural areas, compared to urban areas. Vulnerable populations, such as those

with a disability, lower incomes and/or lower educational attainment, are also

less likely to have access to a phone. Male respondents are more likely to own

phones than female respondents. So we felt that surveying by phone can

introduce a gender bias. Therefore, researchers must be cautious in case of

using a phone survey as a tool for collecting data, especially for

gender-sensitive studies.

4. We found that building rapport with the respondent and

developing a relationship of trust in case of a phone interview requires extra

effort because when enumerators phone the respondent and introduce themselves,

it may make challenging to build a relationship of mutual trust.

5. Though we can collect open-ended responses from the

participant, the telephonic interview does not have the opportunity to

understand the non-verbal cues of the participants. We also noticed

that poor network connectivity, voice breaks, and call drops may disrupt the

interview. In this case, to maximize the chances of the respondent

staying on the line to complete the survey, phone surveys must be short and

sharp, ideally around 10-20 minutes in length.

6. Phone surveys offer the possibility of high-frequency

data collection because carrying out repeated face-to-face surveys of the same

population is a complex and expensive exercise. In this case, high-frequency

phone surveys allow for the collection of regular, real-time insights on the

same population over a period of time. Hence, phone surveys can be a good

choice for studying how people are faring in a dynamic situation such as the

Covid-19 pandemic.

7. As phone surveys are short, many researchers might

wrongly perceive that ethical and research approvals are optional to conduct a

phone interview. But to ensure that survey protocols are ethically sound and

referral procedures are in place, it is as important as ever to obtain consent

from participants, but this must be done verbally rather than in person.

8. We found that explaining the project to a household and

collecting their consent in writing before the survey takes place is easier in

the case of face-to-face surveys in comparison to phone surveys. Therefore, it

is important to invest extra effort in ensuring that participants understand

the research objectives before they agree to participate.

9. We found that there may also be issues with privacy, as

the enumerator cannot be sure that no one is listening to the call on the other

side. This means it is not appropriate to discuss very sensitive subjects in

phone surveys.

10. Choosing an appropriate length of phone surveys is very important for quality data collection. However, the literature is somewhat mixed on this but reaches a consensus that phone surveys should be shorter than in-person surveys. Phone calls duration could be maximum 20-25 minutes, but in-person surveys could last for hours.

From the MOMODa’s experience, it can be concluded

that collecting data through mobile phones has been very beneficial during the

time of the Covid-19 pandemic as conducting face-to-face surveys was not

possible due to lockdown and social distancing. But face-to-face surveys cannot

be perfectly substituted by mobile phone surveys. As mentioned above, mobile

phone surveys have a number of limitations and are suitable only for some types

of surveys and under certain conditions. These need to be carefully considered

when deciding which method to choose.

0 Comments